In November 2010 I photographed aging prisoners in Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana. After the GSA meeting in New Orleans I drove 150 miles through the wetlands, past Baton Rouge, then north up Highway 66. The facility was surrounded by 12-foot razor-topped chain link fences and sentry towers, and before passing through the gates, armed guards searched my car. After entering the facility I had an introduction from Assistant Warden Kathy Fontenot. I toured the facility in a prison vehicle with an officer, Major Joli Dardeaux, who knew most of the inmates and took me to meet the oldest.

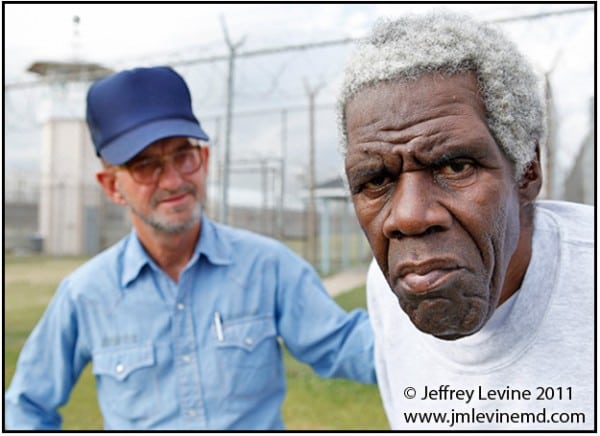

At 18,000 acres, the prison is the largest in the nation, housing over 5,000 inmates. It is roughly the size of Manhattan and surrounded by woods, swamps, and the Mississippi River. It was named after the African country from which many slaves were transported to serve in America’s plantations. Nearly 74% of Angola’s prisoners are serving life without parole, and destined to grow old and die there.

For the first time history America is faced with the dilemma of aging prisoners. According to a report by the National Institute of Corrections, elderly inmates represent the fastest growing segment of federal and state prisons. From 1990 to 2001 prisoners over age 50 tripled from 33,499 to 113,358, or 8.2 percent of the total inmate population.

To accommodate aging prisoners, Angola Penitentiary built the R.E. Barrow Treatment Center which houses severely physically impaired inmates and a hospice unit. The Center contains a ward of twenty-four beds, plus special rooms reserved for the dying. There is also a volunteer program where inmates feed and assist the sick and physically impaired.

I spoke to Scotty Thibodeaux, a volunteer serving two life sentences for double murder. He told me that working with elderly and dying inmates humbled him. He talks to patients and provides shaving, feeding, and assist with dressing changes on wounds. “Once they die, it hurts,” he says. “Working in the Center made it dawn on me how fragile we humans are.”

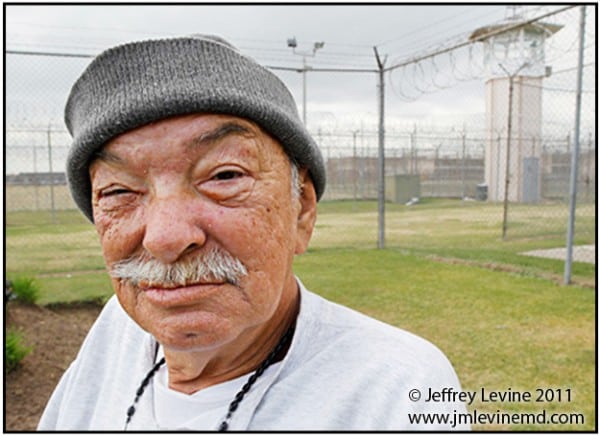

After visiting the Treatment Center we drove past armed guards on horseback watching over field workers. My guide brought me to the dormitory which housed older and physically dependent prisoners, where I met Mr. Bourgeois – a sex offender in his nineties who is serving “life plus 35.” The unit had double bunks with prisoners needing adaptive devices assigned to lower beds. Mr. Bourgeois told me his biggest fear was being beaten up by younger inmates.

Some experts refer to a “criminal menopause,” arguing for early release of older inmates who are considered low-risk for returning to criminal activity. In a weak economy, they cite cost-saving value of releasing low-risk inmates, allowing them to serve the remainder of their sentences in the community. However, the value of geriatric release programs must be weighed against public safety and costs related to other programs for their care.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

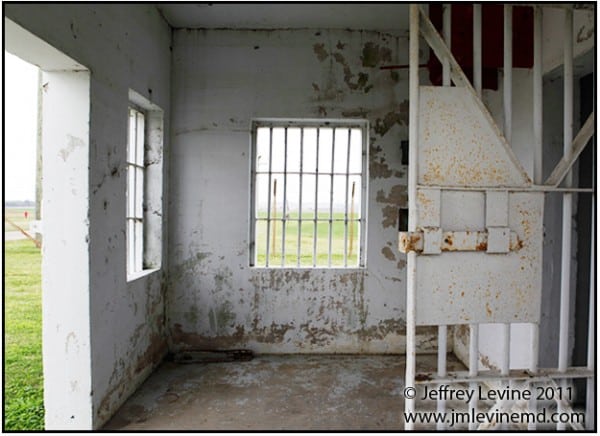

Note on the photos: The old facility pictured in the slideshow is known as the Red Hat Cell Block, the former prison unit reserved for the most dangerous and violent inmates in the Angola Penitentiary. It was called the Red Hat block because when these prisoners worked the fields they were required to wear red hats for identification. It is no longer used and is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

For an excellent reference on the aging crisis in American prisons read this book: Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections, by Ron Aday.

Related posts:

The Angola Museum, operated by the nonprofit Louisiana State Penitentiary Museum Foundation, is the on-site prison museum. Visitors are charged no admission, but may make a donation if they wish.