This past spring I completed requirements for recertification in Geriatric Medicine. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) requires recertification every ten years, and this is my second recertification – marking twenty years since first passing the test after completion of geriatric fellowship in 1986. This makes me one of a very small number of physicians in the United States certified in this medical subspecialty. The last figures, released in 2005, show only 7,600 board certified geriatricians. With an estimated need of 20,000 geriatricians, and in a socio-demographic change never seen in American history, our country is moving headlong toward a crisis that has been underappreciated in our medical schools, and inadequately addressed in our healthcare reform agenda.

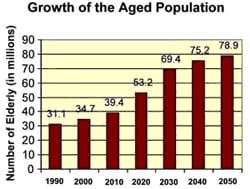

The over 65 age group is currently the most rapidly growing sector of American society. By 2030, 20% of our population will be 65 and older, up from 12.4% in 2000. At the same time, the number of physicians with certification in Geriatrics is predicted to drop. Already down from a high of 9,256 in 1998, Geriatrics continues to be an unpopular specialty for American medical school graduates.

Board Certification in Geriatric Medicine

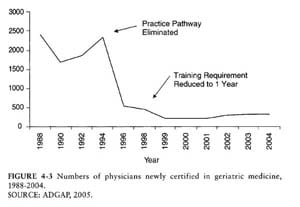

Board certification is granted by the ABMS, a not-for-profit organization which assists specialty boards in developing standards for the 24 approved specialty boards. The path to certification in geriatrics can be taken through initial certification in either Family Medicine or Internal Medicine, followed by a one-year fellowship in a program approved by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which is responsible for post-MD training programs in the United States. When formal Geriatric fellowship training first began in the 1980’s, the initial requirement was two years of training. In 1998 the leadership of the American Geriatrics Society recognized that few physicians were choosing geriatrics as a career path, and the requirement for fellowship was shortened to one year in the hopes of expanding the applicant pool. Unfortunately this strategy has not worked, and Geriatrics is still struggling for qualified numbers of applicants. In addition, many of my colleagues feel that shortening the fellowship requirement has devalued the training. Some fellowship programs still maintain the two-year requirement even though the ACGME requires only one.

Board certification is granted by the ABMS, a not-for-profit organization which assists specialty boards in developing standards for the 24 approved specialty boards. The path to certification in geriatrics can be taken through initial certification in either Family Medicine or Internal Medicine, followed by a one-year fellowship in a program approved by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which is responsible for post-MD training programs in the United States. When formal Geriatric fellowship training first began in the 1980’s, the initial requirement was two years of training. In 1998 the leadership of the American Geriatrics Society recognized that few physicians were choosing geriatrics as a career path, and the requirement for fellowship was shortened to one year in the hopes of expanding the applicant pool. Unfortunately this strategy has not worked, and Geriatrics is still struggling for qualified numbers of applicants. In addition, many of my colleagues feel that shortening the fellowship requirement has devalued the training. Some fellowship programs still maintain the two-year requirement even though the ACGME requires only one.

Geriatrics was not always considered a specialty by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Initially in 1988, specialization was granted in the form of a “certificate of added qualifications,” or CAQ. In 2006 the ABIM formally recognized geriatrics as a subspecialty of Internal Medicine – a step the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) hoped would elevate the value of geriatrics to the general public and professional groups.

Another change in certification was the “practice pathway” which has since been eliminated. When certification was first established there were two pathways leading to eligibility the geriatric boards. The first was the “practice pathway,” where an applicant with medical practice experience could take the board examination, the second was completion of an accredited two-year fellowship. In 1994 the practice-pathway was phased out, leaving only those persons who completed formal geriatric fellowship training eligible for the boards. Unfortunately this caused a steep drop in persons becoming certified in Geriatrics.

The Shortfall of Geriatricians

Now that my second recertification is complete and I reflect on two decades of geriatric practice, I observe trends that are unsettling. I frequently see the results of mismanagement of medical conditions associated with old age by a medical system that is not equipped to cope with the needs of this demographic. I am often consulted by family members pleading for access to resources which do not exist. I also observe medical students bypassing geriatrics and other primary care specialties for technologically centered specialties or those with a better “life-style” component. Geriatrics and the needs of a rapidly growing elderly population are barely visible on the map of today’s healthcare reform agenda. We are growing a society with more elderly persons than ever before in our history – elders who are active and socially connected, and elders with multiple chronic illnesses that need management from both a medical and ethical standpoint. We are all on the way to becoming old, and I am concerned that the society we are building will be incapable of meeting the needs of its citizens.

Now that my second recertification is complete and I reflect on two decades of geriatric practice, I observe trends that are unsettling. I frequently see the results of mismanagement of medical conditions associated with old age by a medical system that is not equipped to cope with the needs of this demographic. I am often consulted by family members pleading for access to resources which do not exist. I also observe medical students bypassing geriatrics and other primary care specialties for technologically centered specialties or those with a better “life-style” component. Geriatrics and the needs of a rapidly growing elderly population are barely visible on the map of today’s healthcare reform agenda. We are growing a society with more elderly persons than ever before in our history – elders who are active and socially connected, and elders with multiple chronic illnesses that need management from both a medical and ethical standpoint. We are all on the way to becoming old, and I am concerned that the society we are building will be incapable of meeting the needs of its citizens.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *