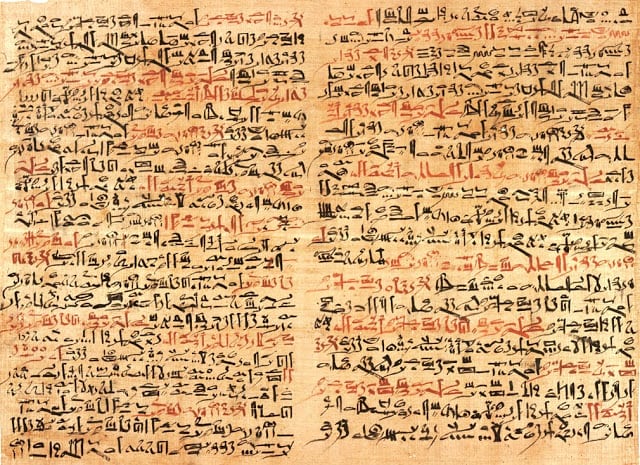

The art of medicine is as old as human civilization, and what we think is new has often been done before. When researching the history of wound care I came across an interesting historical antecedent to today’s palliative care practices. I found it in the library of the New York Academy of Medicine in Manhattan, in a translation of an ancient Egyptian medical scroll, the Smith Papyrus, pictured above.

During the American Civil War, an Egyptologist named Edwin Smith acquired the scroll and brought it to the United States where it subsequently found a home at the Academy on Fifth Avenue. The document is roughly fifteen feet long and three feet wide, and has writing on both the front and back. The scroll is made of papyrus, an ancient form of paper made from fibers of a plant native to the Nile region. Written with a reed pen, the text is a simplified form of Egyptian writing known as hieratics. The script differs from formal hieroglyphics which were more complex and painstaking to write. Documents reflecting daily mundane affairs were recorded in hieratic script, whereas temples, monuments, and official documents were written in the more readily recognizable hieroglyphics.

Tradition holds that information in the Smith Papyrus was passed down from the time of the Pyramids, nearly 5000 years ago. The original author might have been Imhotep, high priest to the sun god Ra and medical advisor to the pharaohs, and the earliest physician in human history whose name we know. Throughout ancient Egyptian civilization, Imhotep was viewed as a god who obtained his knowledge of medicine directly from the heavens. The Papyrus contains 48 clinical case presentations, each reflecting traumatic injury or other pathologic lesion. The cases are organized anatomically according to location, and many of the cases are devoted to wounds of the skin. Others include tumors or ulcers, and injuries to bones and joints.

Ancient Egyptian physicians were surprisingly sophisticated. For example, they recognized that the brain controlled bodily movement, with injury to one side of the brain leading to weakness of extremities of the opposite side. Physicians also realized the importance of examining the heart and pulse when determining the extent and nature of a disease and injury. What surprised me was a system where the physician determined which patients to treat and which were hopelessly ill and did not merit curative treatment.

Each case in the Smith Papyrus contains physical observations of the disease or injury followed by a diagnosis, and a prognosis which determined the level of treatment offered. James Henry Breasted, the first translator of the document, called this prognosis the “verdict.” There were three possible verdicts rendered by the Egyptian physician, the most favorable was a lesion or disease that can be treated and most likely cured. The next and more serious verdict determined that the injury or disease can be treated but may not be cured. Finally, there was the verdict of a hopeless prognosis, where curative treatment was not offered.

Medicine today is quickly evolving, and there are lessons to be learned from the ancient Egyptians. First, the physician has been dethroned from the godlike status they once held. The days in which sacred information was passed down into the hands of a select few are over, as medical knowledge is available to anyone with a handheld device. The scientific knowledge and values transmitted by mass media have formed a culture whereby sickness, aging and death are lifestyle choices rather than natural components of human existence. Many caregivers, though equipped with the knowledge to recognize medical futility, are either untrained or unwilling to have the difficult conversation with patients and families explaining that curative treatment will not work.

Part of the physician’s role in ancient Egypt was to recognize medical futility and act accordingly. How different this is in today’s society, where illness and death are often viewed as failures of the medical system. A recent report by the Institute of Medicine underscored the “perverse financial incentives” that deter implementation of humanistic end-of-life principles and encourage costly heroics that may incur additional suffering. Palliative care means facing the facts and offering alternatives that may not be in accordance with cultural preconceptions. Part of the solution recommended by the IOM is introducing palliative care early in the medical curriculum, impressing upon young doctors the importance of not only recognizing, but making appropriate decisions when cure is not the goal – much like the practice of physicians in ancient Egypt.

Reference for this post was: Levine JM. Wound care in the 21st century: Lessons from ancient Egypt. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2000; 1: 224-227.

Learn more about the history of wound care in my webinar archived on the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) website: History of Wound Care: Past, Present, and Future.

.