Myiasis is the medical term for infestation with the larvae of a fly, also known as maggots. The image of maggots in modern society is the exact opposite of health and cleanliness. Indeed, unintended myiasis in a healthcare facility is a frequent precursor of a negligence or malpractice lawsuit. Despite their repugnant image, there are companies that sell fly larvae for use in the care of chronic wounds. Personally, I would not recommend larval therapy as there are much more modern approaches available to wound healing, but there are some practitioners who prescribe them.

During my medical career I encountered human myiasis  on several occasions. The first was in the autopsy room of the New Jersey Medical Examiner during my medical school pathology rotation. A body was found in someone’s backyard that was infested with fly larvae. To kill the insects, the pathologist poured kerosene on the affected areas, and I will never forget the sight of the squrming little worms as they

on several occasions. The first was in the autopsy room of the New Jersey Medical Examiner during my medical school pathology rotation. A body was found in someone’s backyard that was infested with fly larvae. To kill the insects, the pathologist poured kerosene on the affected areas, and I will never forget the sight of the squrming little worms as they

were flushed down the drain of the autopsy table.

I had the occasion to observe human myiasis several more times in the emergency room. For example, I recall a homeless heroin addict who came in for swollen legs with gaping ulcers – the result of years of dirty needles and malnutrition. On examination the wounds were clean and pink, but there was something moving in the wound bed. The lesions were infected with fly larvae, or maggots. What was unmistakable was that the wounds were clean and odor free.

Maggot therapy was once a widely accepted treatment for chronic, nonhealing wounds. Physicians throughout history noted that when wounds are infested with maggots they prevent infection and accelerate healing. Prior the development of antibiotics such as sulfanilamide and penicillin in the 1940’s, maggots were widely and successfully used for osteomyelitis, leg ulcers, tumors, and abscesses.

Maggots and their Mechanism of Action

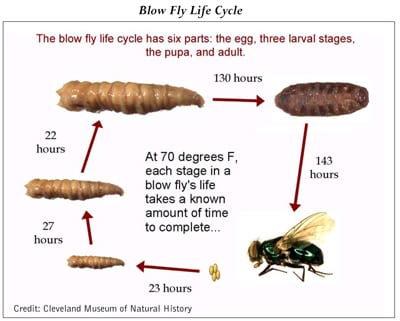

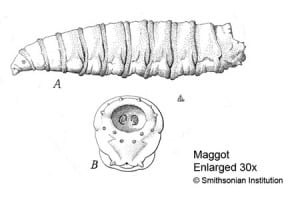

A maggot is small worm which is part of the life-cycle of the blowfly. The adult female fly lays eggs in a damp, soiled area, which hatch in 8 to 24 hours producing larvae, or maggots. The larvae have a pair of hooks near the mouth which attach to the substrate while it feeds. After shedding its skin several times, each larva becomes a mummy-like pupa, which later pops open allowing the adult fly to emerge.

The mechanism of action for maggot therapy is multifold. The larvae feed on dead tissue and cellular debris found in necrotic wounds, and secrete proteolytic enzymes. The maggots also assist in killing bacteria through a number of mechanisms including bacteriocidal byproducts of the larval gut, and chemical secretions that change the pH of the wound bed. Some studies have suggested that myiasis directly stimulates granulation tissue through physical stimulation or chemical mediators.

There are many strains of blowfly whose larvae thrive in flesh, but only a few are used for medical purposes as undesirable species can ingest living tissue as well as necrosis and waste. Maggots for wounds are also termed “maggot debridement therapy,” or MDT, and is not covered by Medicare. One commercially available species is Phaenicia sericata, available by prescription and sold by the vial, each vial containing a choice of either 250 – 500 eggs, or 500 – 1,000 eggs. The vial comes with gauze and sterile food containing soy protein and brewer’s yeast, and the eggs will hatch within 12 hours of preparation.

The user is instructed to apply the eggs and larvae at a dose of 5 -8 per square centimeter of wound covered by loosely packed gauze. The wound is then covered by a breathable absorbent pad, and should be cleaned and re-dressed every 48 hours. The package insert warns: “If left longer than 48 hours, the risk of maggots escaping increases.”

Natural Maggot Infestation of Wounds in Humans

Whatever your opinion of medical maggots, the occurrence of natural myiasis in a wound is undesirable, primarily because it signifies neglect through exposure. The naturally infesting maggot may be one of the many harmful species which eats living flesh and does not assist with healing. Medical maggots are applied and removed in 48 hours – long before the larvae is allowed to emerge into a living blowfly 10 to 20 days later. In contrast, naturally occurring maggot infestations offer no such control over transformation into adult flies.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A reference for this blog post was Sherman RA et al. Medicinal Maggots: An Ancient Remedy for Some Contemporary Afflictions. Ann Rev Entomol 2000; 45: pp 55-81.

Thank you for describing therapeutic and non-therapeutic (natural) myiasis, and for sharing your views about each.

For the sake of clarity and accuracy, I would like to correct two common misconceptions: 1) Maggots on a corpse do not constitute myiasis. Myiasis is a maggot infestation on a living host. 2) “Medicare” usually does reimburse for maggot therapy. Like private insurance, each Medicare subcontractor has the right to define those treatments that will or will not be covered, but most Medicare subcontractors have no prohibition against covering maggot therapy.

In fact, the American Academy of Professional Coders last year noted Aetna’s policy statement that “it considers medical maggots medically necessary for the debridement of any of the following non-healing necrotic skin and soft tissue wounds: pressure ulcers, venous stasis ulcers, neuropathic foot ulcers, non-healing traumatic or post surgical wounds” (http://news.aapc.com/index.php/2009/11/aetna-medical-maggots-are-medically-necessary/).

As far back as 2004, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included maggot therapy among its defined and acceptable methods of wound debridement (CMS Manual System, Pub. 100-07 – State Operations Provider Certification)

Medicare’s embrace of maggot therapy should be no surprise. DHHS’ Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ – whose guidelines and recommendations often form the basis for Medicare’s policies) included maggot therapy in Lyder & Ayello’s chapter (#12) on Patient Safety and Quality – An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses: “Biosurgery (maggot therapy) is another effective and relatively quick method of debridement This type of debridement is especially effective when sharp debridement is contraindicated.”

You are quite correct that “there are much more modern approaches available to wound healing.” But for my own practice, I choose what works best for the individual patient, not what is most modern. When my patients can not tolerate what might otherwise work best (for example, surgery); or when they have already failed two or three “modern” treatments, I offer maggot therapy because I know it is as effective as it is old. Clinicians who delay maggot therapy until it is time to amputate may be saving 40-50% of those limbs (according to published reports), but I believe they are doing their patients a disservice by delaying that treatment.

So, Dr. Levine, hopefully your real reason for not using maggot therapy is that you do not need it; you are able to treat your patients’ wounds quickly and effectively with other readily available treatments. Perhaps your patients do not suffer from “chronic wounds” (at least not once you get on their case). That would be wonderful for you and your patients. But since most of my patients have not had such good fortune, I remain grateful for the existence and availability of medicinal maggots.

Respectfully yours,

Ronald Sherman, MD

Director, BioTherapeutics, Education & Research Foundation

Laboratory Director, Monarch Labs

Clinic Physician, Orange County Health Care Agency

Thanks Dr. Sherman for your clarification and thoughts on maggots for wounds. I must say that I really enjoyed your article that I used as a reference for my blog post, and would recommend it as a primary source for anyone interested in this topic.

My mind is still unchanged, however, regarding prescribing them for my patients. Perhaps it’s just my feelings on having insects on the body, and the ready access to alternatives.

JML

I think that greed for high profits has a lot to do with how medicine in often practiced. Most U.S. doctors dismiss maggot therapy because there is so much money to be made with invasive surgeries.

Most medical schools have a pro-surgery, pro-prescription drug bias in what they teach students. After all special interests including big pharma own most medical schools.